Selection: Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt (Lower Egypt, extract)

. . .

Track List

A1. Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt – 16:12

B1. Japan – 3:22

B2. Aum/Venus/Capricorn Rising – 14:46

Artists

Pharoah Sanders, tenor, alto sax, piccolo, voice; Dave Burrell, piano; Sonny Sharrock as Warren Sharrock, guitar; Henry Grimes, bass; Roger Blank, drums; Nat Bettis, percussion; producer, Bob Thiele; recorded Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, November 15, 1966, released October 1967.

Recorded shortly after Sanders session under Don Cherry for Blue Note – Symphony For Improvisors 4247 and Where is Brooklyn? 4311. The album also marks guitarist Sonny Sharrock’s first appearance on a record, featuring splendid avant-garde comping

Music

Critical acclaim: One writer referred to Tauhid as “the first and best of Pharoah Sanders’s Impulse albums.” All About Jazz, called Tauhid “arguably the finest statement in [Sanders’] astral oeuvre,” After the hype, AllMusic notes that “Sanders’ tenor appearance doesn’t saturate the atmosphere on this session; far from it. Sanders is content to patiently let the moods of these three pieces develop”. Pitchfork gets to the heart of the album: “the pieces are suites that play like seances, with movements billowing and unfolding of their own accord. The group’s unity is powerful, creating a spiritual atmosphere that casts a spell from the opening bars.”

The centre piece of the album is the sixteen minute huge canvas of Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt, of which I have included the second half as a taste, and not the whole piece, for that you need to go find the whole album. The whole piece assembles very slowly, building an atmospheric landscape, sounds of nature painted largely by sound effects, which evolves through ethno-percussion organically into a rhythmic, hypnotic trance. Pharoah smears the landscape briefly with the tenor sax, until it fades as slowly as it emerged. What Rudy at the recording desk made of it I’m not sure, there must have been little much like it in 1966. It still sounds modern by experimental music standards four decades later.

Its a great album, that demands concentration and protected listening time.

Vinyl: released originally as AS-9138 (1967) – this official reissue by Universal, Germany, LC00236 06007 5397092 My copy was shipped from Germany through Belgium to UK, not seen any on local distribution yet.

Recorded by Van Gelder, original tapes will have passed through his hands into the custody of Impulse, and from there, who knows. Finger points at MCA or GRP. No recording source is declared for this edition, no claim to mastering from original tapes. As an official release by Universal, who hold the rights, and would own the tapes if they still existed, one must assume the worst, that the original tapes no longer exist, and this is mastered for vinyl – albeit expertly – from an archive digital file.

Without an original Impulse for comparison (virtually never seen in UK), I can’t say for sure which sounds better, but I find this album quite a satisfying listen, nothing harsh or digital in artefact, nicely engineered stereo dynamics, Sharrock’s comping is a treat, and just about silent inky black vinyl, that allows you to concentrate on the music without vinyl surface noise.

If I saw an original Tauhid copy in top condition, I would still grab it. People talk down later Impulse, me included, but I recently found some original Impulse editions (black red rim) of other Pharoah titles – Thembi, Live at the East, and Black Unity – and they Sound Great To Me™.

More thoughts about vinyl digital sources in Collector’s Corner. (No, its not a rant against digital!)

Inner Sleeve” Universal edition insert copied from the original inner gatefold.

Harry’s Place

Welcome return of our time-travelling jazz-paparazzi Harry M, whose time-machine glided through Montreux in 1970 to capture Sonny Sharrock in action. Hold it just there, Sonny, I need to load another roll of Tri-X, hold it, OK, and Action! Nice.

Photo Credit © Harry M

Collector’s Corner: the Tauhid release history

Impulse initial release of Tauhid on the orange /black label in 1967 was followed by regular repressing into the 70s with updated labels, initially with VAN GELDER metal. As often seems the case, RVG metal replaced by another engineer re-master with the black/neon logo label , possibly triggered by Van Gelder signing an exclusive deal with Bob Theile after he left Impulse. Ed Michel says: “No more VAN GELDER for you!“

Over the last decade the album has not fetched record-breaking prices. Many of the later pressings sold for little over $30, it was not a trophy by collector standards, and only more recently does it seem to have gained traction, since Pharoah’s high profile resurgence with Floating Points.

The story of Tauhid re-emerged in the early 90s, entering the era of the Compact Disc: “digitally re-mastered by Robert Stoughton at MCA Music Media Studios; ℗ 1993 MCA Records, Inc. & © 1993 GRP Records, Inc. Manufactured by Matsushita Universal Media Services, Pinckneyville, IL. a joint venture between Universal Music & Video Distribution, Inc. and Panasonic Disc Services Corp.”

“digitally re-mastered by Robert Stoughton at MCA Music Media Studios; ℗ 1993 MCA Records, Inc. & © 1993 GRP Records, Inc. Manufactured by Matsushita Universal Media Services, Pinckneyville, IL. a joint venture between Universal Music & Video Distribution, Inc. and Panasonic Disc Services Corp.”

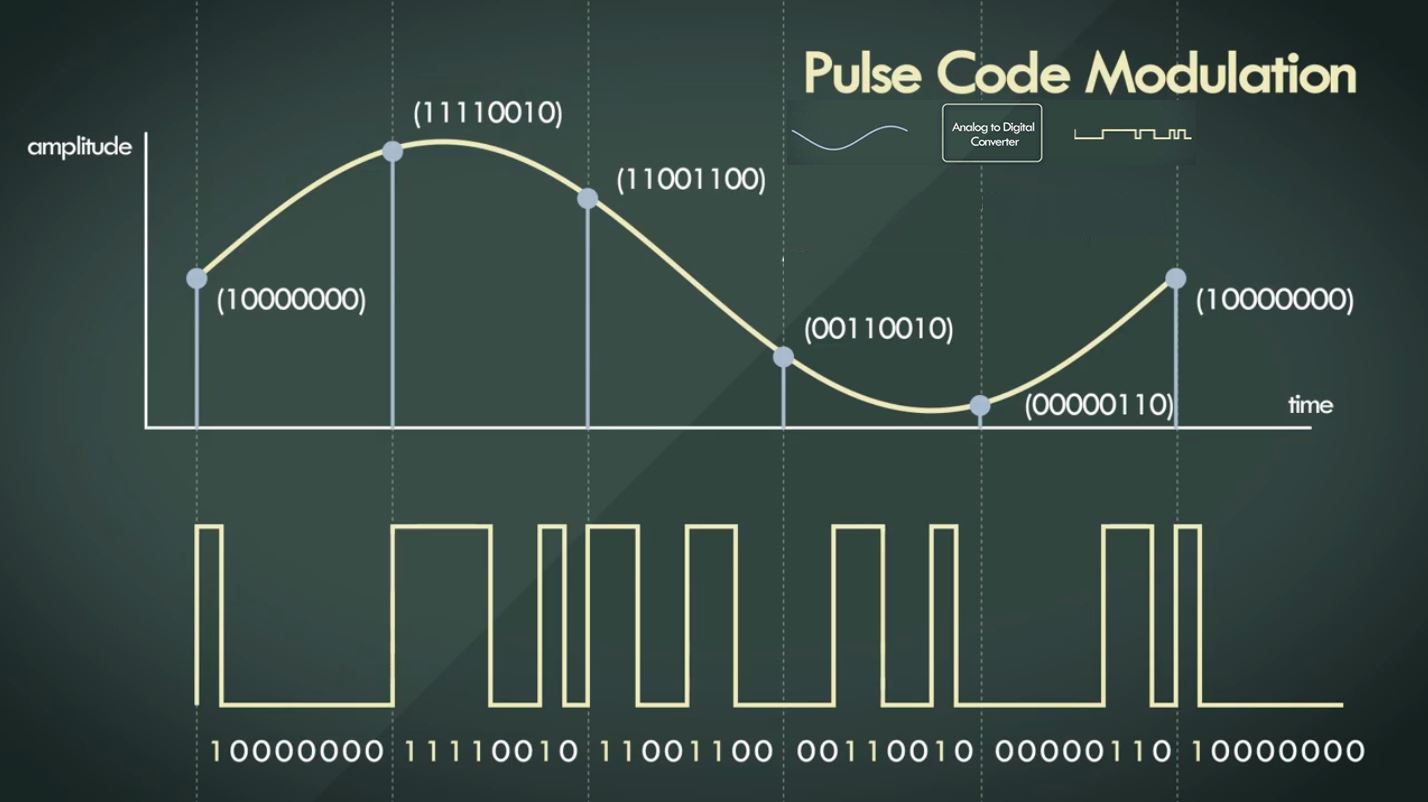

The official digital copy of Tauhid dates from 1993, thirty years ago, using the technology of the time , often still in use, PCM (Pulse Code Modulation) the industry standard digitizing format for Audio CD (“Red Book” specification 44.1 khz/16bit published 1982 revised 1987). The source of the digital transfer in 1993 can only be the original master tapes, or at least a working copy tape of those original tapes.

The only vinyl editions since the late 70s are by Anthology (2017, left), a specialist vinyl reissuer of digital recordings, and an unlicensed reissue from the Russian bootleg label Audio Clarity (probably from a download). The rest are all periodic CD reissues, no technology advancement on 1993 CD Audio format. In any event, upscaling a 44.1khz/16bit file to higher resolution doesn’t capture any more information.

The only vinyl editions since the late 70s are by Anthology (2017, left), a specialist vinyl reissuer of digital recordings, and an unlicensed reissue from the Russian bootleg label Audio Clarity (probably from a download). The rest are all periodic CD reissues, no technology advancement on 1993 CD Audio format. In any event, upscaling a 44.1khz/16bit file to higher resolution doesn’t capture any more information.

There is no evidence of the use of the original Tauhid tapes in the last thirty years. Impulse were a prominent jazz victim of the LA back-lot fire. The tapes have not suddenly been rediscovered, just modest silence, the best we can honestly expect. What does still exist is a digital file.

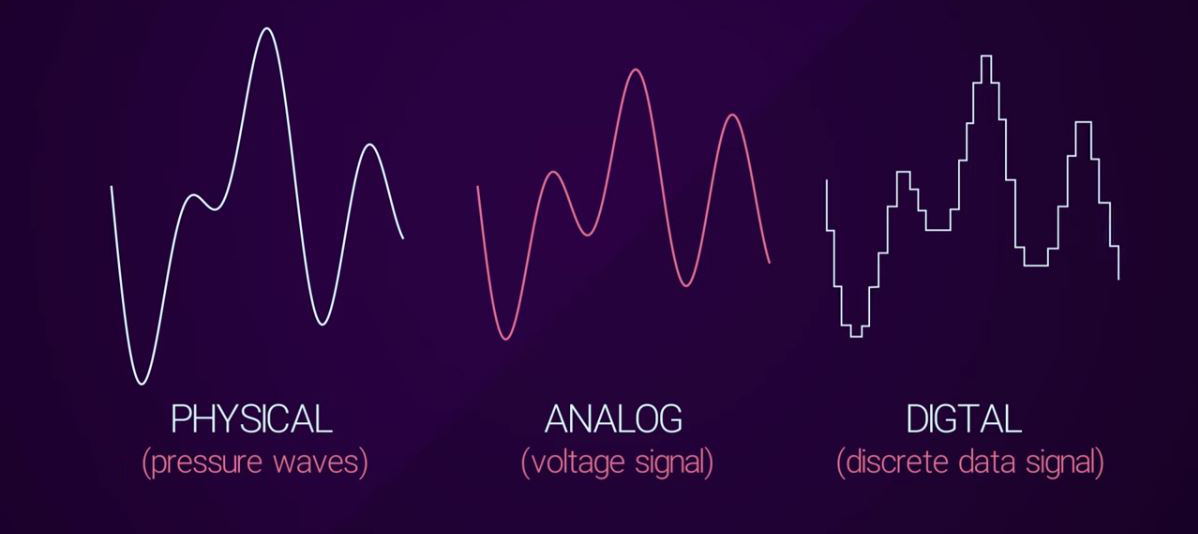

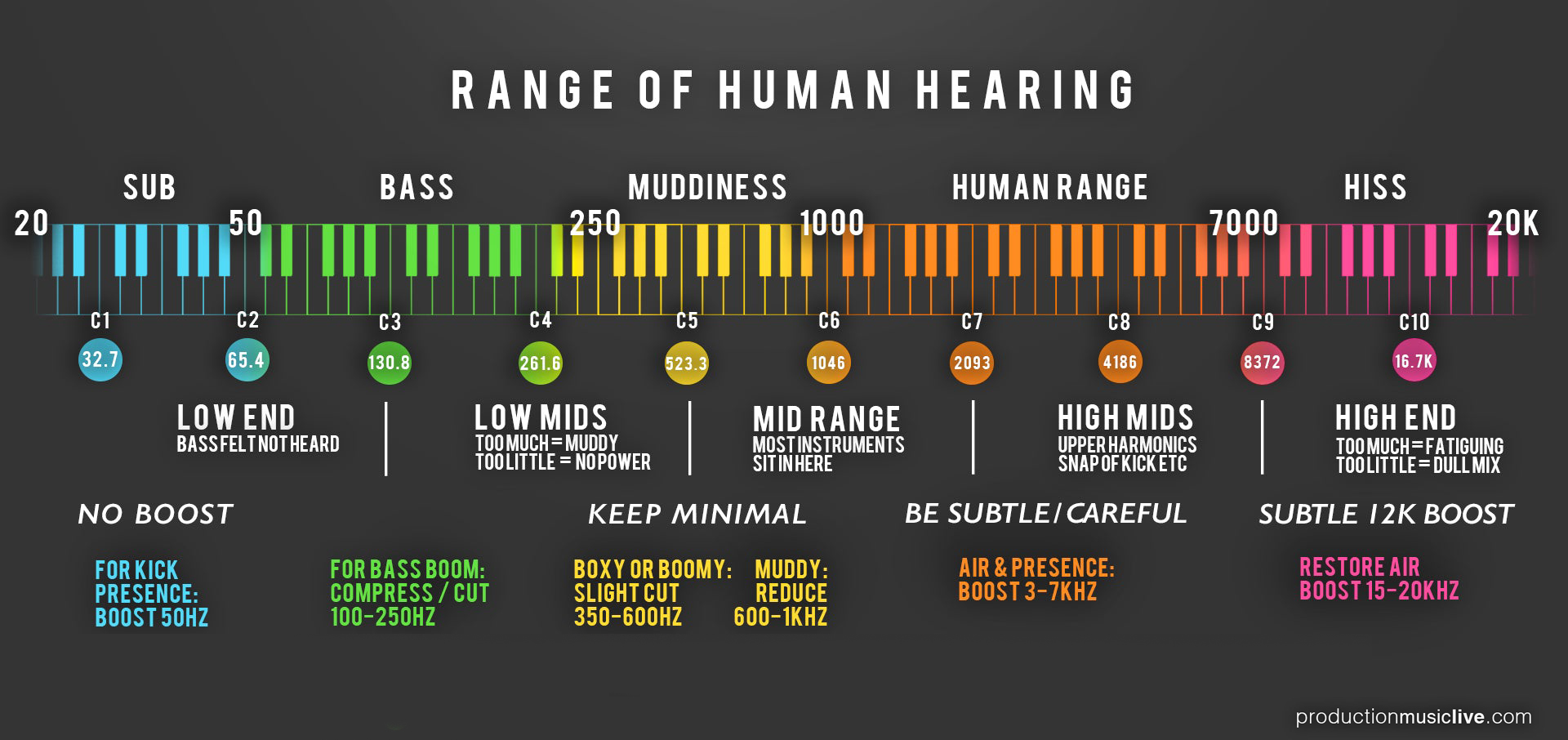

Short Digital Primer: musical instruments generate PHYSICAL pressure waves, which listeners hear. Microphones capture and tape recorders transform those pressure waves into an electronic voltage signal stored on magnetic tape, we call ANALOG. Those analog signals can be transformed into binary data stream of zeros and ones stored on a disk-drive, we call DIGITAL.

In the 1980s, entering the digital era, PCM encoding – Pulse Code Modulation, became the industry standard for sampling, electronic storage and transmission of audio data. It’s worth a shallow dive to understand the technology.

PCM converts the amplitude of an analogue signal into binary code.

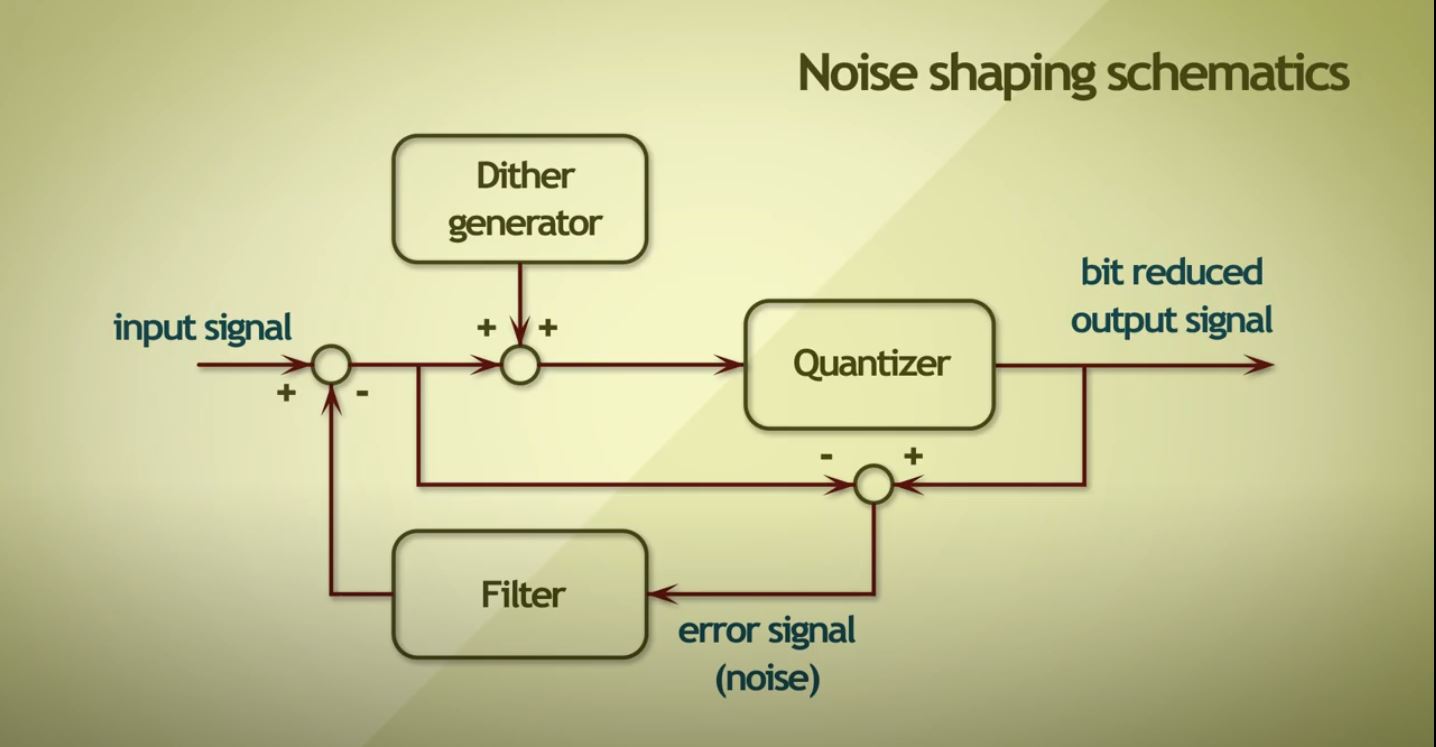

PCM digital data lends itself to near-unlimited digital processing of audio information: compression and limiting (in common with vinyl), quantization (filling gaps between samples), high and low pass filtering, eliminating those pesky top frequencies “we can’t hear”, dithering, sound envelope shaping, white noise remapping, frequency boosting.

An example of signal processing, in which low gain signal (a quiet bit) has noise added, to cover up other digital artefacts.

Finally, the processed PCM file can be output to any digital audio output format: to CD (WAV or AIFF), reduced file-size for streaming (MP3), and most important, remastering for acetate cutting, to fit the physical requirements and limitations of vinyl. Derivatives of PCM files are also the bootleggers undeclared source for unofficial reissues.

Modern equipment today can record digitally in much higher resolution, store more information, even process it to advantage (boosting db of selective frequencies), but sadly, it can not go back in time. The sound quality is only as good as the source capture in 1993. What was lost transferring the original analogue tape to the audio-workstation PCM conversion is lost forever.

In the case of missing original tapes, this is where a lot of our music legacy rests. Not the “Which is best, analogue or digital?” Hoff-men argument, but for some music, it is digital or nothing.

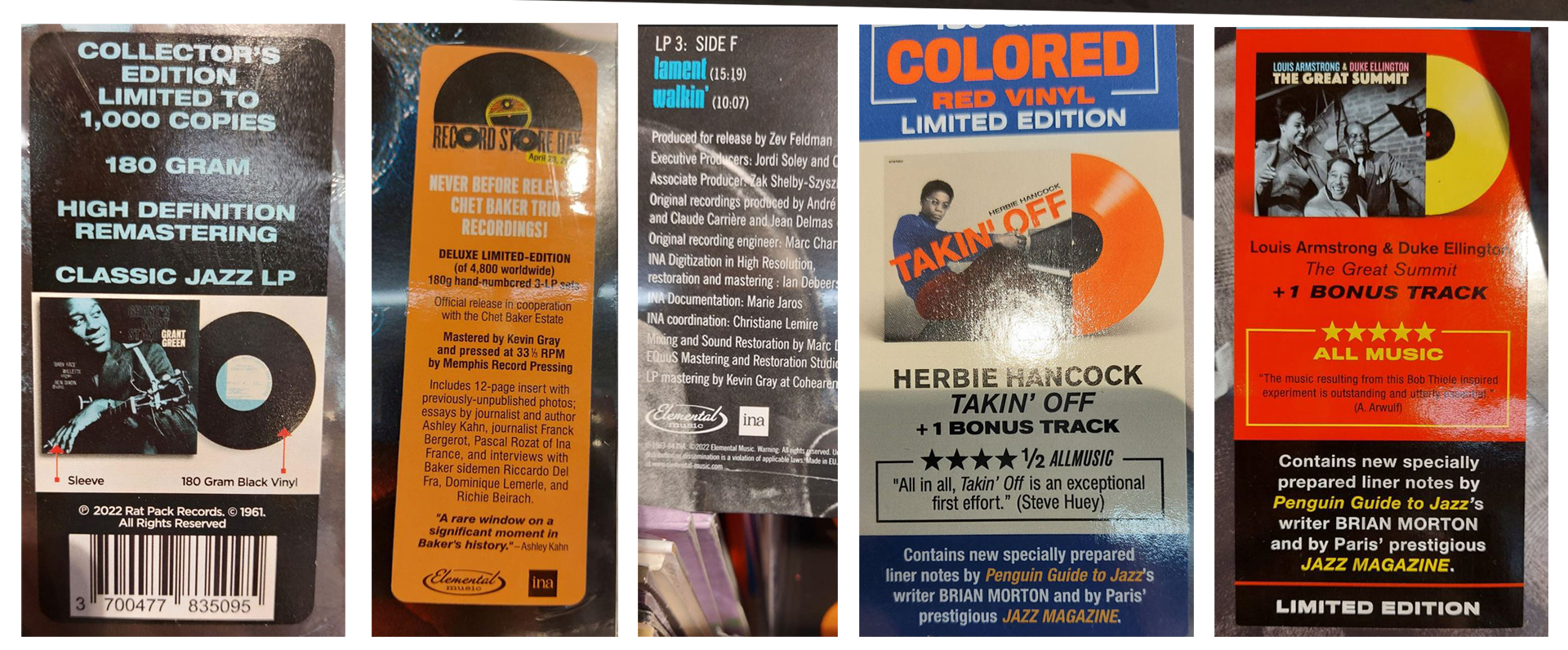

Back to the bigger picture of the “vinyl renaissance” and its Hype Stickers – First time on vinyl! 180-gm audiophile!, Limited Edition! From the original tapes! – Audio Window Dressing, strangely, usually no mention of sources.

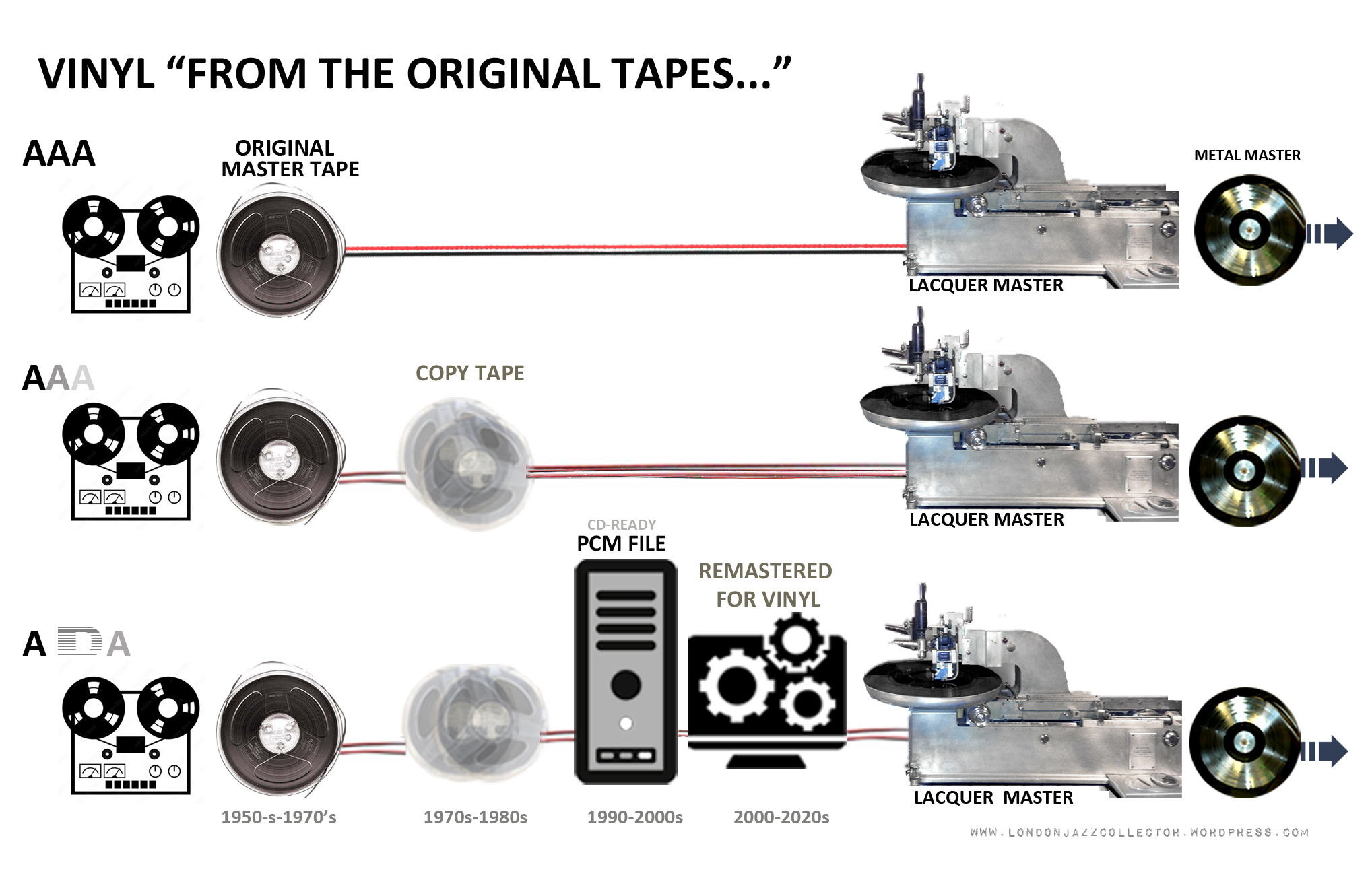

I have done another of my thought-graphics … simplified for clarity, over-simplified maybe. There are many other variations, like needle-drops, but this sums it up for me the ways in which original recording tapes connect to vinyl, throw your own spanner in the works if you like 🙂

Everything is “from the original tapes”, but only a select few are mastered from the original tapes – the All Analogue process (AAA). Over the decades, the source of vinyl reissues became copy analog tape, notably, most overseas edition such as Japanese pressings. They were still in a sense All Analogue, but with an intermediate tape generation step down (AAA). Then in the mid-80s, with the arrival of the compact disc, the music world entered the digital era and the new musical ringmaster, the digital audio engineer.

The ease with which digital files can be transferred to vinyl – Analogue> Digital> Analogue (ADA), officially and unofficially, is evident everywhere on the Hype stickers, and the vinyl reissue industry depends commercially on audio window dressing (AWD). Funnily enough, in the 90s, record companies were boasting records were digitally mastered.

An engineers guide how to improve recordings digitally: digital transformation and t-polishing. You may ask, why is it necessary? Just because you can doesn’t mean you should.

A lot of the The vinyl reissue industry is hoping no one will be aware of the intermediate digital stage, or what has been done to the recording.

I am not an engineer, that should be obvious. I am a collector of original pressings, because I know what I hear, and they sound better to me. Perhaps one day they will make digital editions of these vintage recordings sound even better than original vinyl. I listen to both. We are teetering at the edge, some claim we are already there. I’ll be audiophile-delighted if they could improve, and dump the AWD.

To find out more about the analogue/digital interface, the best educator I have found on the digital processing of audio signals is Akash Murthy, whose numerous Youtube videos( I’ve borrowed a couple of slides) cover every aspect in depth, including all the stuff you didn’t know you didn’t know. https://www.youtube.com/@akashmurthy/videos

I’ve rambled into unfamiliar territory, hopefully it is of interest, welcome to throw in your own thoughts about Pharoah, or the Vinyl Renaissance, digital sources, or anything else vinyl jazz on your mind. It’s always open mic. at LJC

Just don’t touch that dial.

LJC

Interesting read. Just came across a cassette tape of Tauhid while rummaging through a relative’s loft.

LikeLike

Thanks for this enlightening review, had to have a copy; makes a nice pair with the AS series Karma.

Point of interest, is it just me or did you notice that side 2 is mono as is the Tidal stream. If so I can only assume the stereo tape is missing too.

LikeLike

That’s a suprise! I wrote the review shortly after the record arrived, it says “stereo” but I just ran Side 2 through Audacity and the left and right channel histograms are effectively identical. It is definitely not a stereo mix. Duh. There is obviously a story behind this recording, kept under wraps.

LikeLike

The ‘Audacity’ of them!

LikeLike

nice to see you enjoying some of the spiritualism! a fun note about sharrock – he famously HATED his instrument. there is some writing on it somewhere. fascinating stuff.

LikeLike

The sound on the original IMPULSE! release is superb, worth seeking out. I can’t adequately compare my record with the track you have here. How can one do that? The medium is the message.

As I wrote previously,

“TAUHID is one of my favorite albums. Pharoah’s first entry on tenor sax, about four-fifths of the way through the first side (!) is astonishing, like the arrival of a visitor from another planet. The short “Japan” on side 2 is touching in its simplicity but the centerpiece of the album (for me) is the suite of “Aum,” “Venus” and “Capricorn Rising,” where sections of seemingly utter chaos alternate with (Coltrane-like) melodies of remarkable beauty. Pharoah’s ability to evoke yearning and resolution are on full display here. He had a good band on this album, especially in Henry Grimes on bass and Dave Burrell on piano. This was also Sonny Sharrock’s auspicious debut on record. He later appeared on a wide variety of interesting albums. Some in my own collection include Miles Davis’ A TRIBUTE TO JACK JOHNSON, Byard Lancaster’s IT’S NOT UP TO US, Wayne Shorter’s SUPER NOVA and BRUTE FORCE with the band of that name.”

LikeLike