Selection: Senor Blues

. . .

Artists

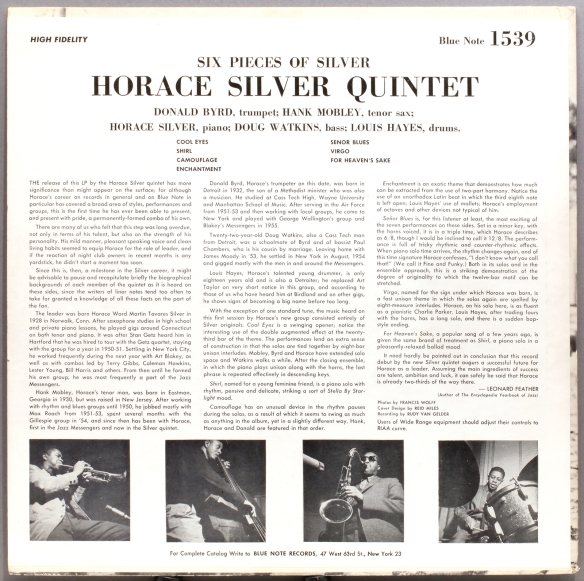

Donald Byrd, trumpet; Hank Mobley, tenor saxophone; Horace Silver, piano; Doug Watkins, bass; Louis Hayes, drums; recorded Rudy Van Gelder Studio, Hackensack, NJ, November 10, 1956.

Music

For Crissake, what more do you want? Mobley, Byrd, Silver, Watkins, Hayes! This is real music: inject it, inhale it, snort it, insert it anyway you like as long as you get it into your life. This is coming to you personally, directly from 1956, unlimited reanimating power embedded in the grooves of fifty year old vinyl, as fresh as if you opened the windows on 1956 and breathed in.

The Vinyl: Another case for DJ Sherlock

However not everything is as it appears. A massive 205 gram vinyl, flat edge, with deep groove both sides, Lexington labels both sides, catalogue number written in large open hand, RVG hand-inscribed initials, the 9M, ear, No INC or R on either label or cover. You might think, an open and shut case Lexington, however there are two discrepencies.

However not everything is as it appears. A massive 205 gram vinyl, flat edge, with deep groove both sides, Lexington labels both sides, catalogue number written in large open hand, RVG hand-inscribed initials, the 9M, ear, No INC or R on either label or cover. You might think, an open and shut case Lexington, however there are two discrepencies.

First, the A side matrix indicates its origin is second master – A1. Observe:

Exhibit 1: The Matrix

A second matrix A-1 is difficult to explain. Why A-1 but not also the side two a B-1? Was it a huge seller that needed remastering? Most Blue Note did not sell in the sort of quantities that exhausted the potential number of mothers and stampers. Pressing was localised to New Jersey so no second master created for a West Coast plant pressing to work with. Perhaps it required a fresh master because the original was damaged in some way soon after its creation? Van Gelder spilled the coffee on it, as happens to my keyboard sometimes.

The sound quality – piercing, vivid sound – is up there with my other Lexingtons. And that waistline, at 205 gram, is inside the range for a Lexington, way heavier than the 1957-61 47 West 63rds (170-190gm) and out of the question for later pressings. I swear on a stack of Fred Cohen Guide to Original Blue Notes, the vinyl dates from 1956, and it is in a cover that was first introduced in 1957, possibly an extended first pressing run and replenished cover stock.

Or perhaps it’s a trick being played by the notorious Blue Note elf, who delights in driving collectors crazy. Did you know that while you are asleep, the Blue Notes on your shelf get together and talk about you?

Another example of a suspect Lexington, the subject of an earlier post. This has everything right, including the cover, except the weight is a skinny 165 gram, the norm for mid Sixties Blue Note NY pressings. Clearly an impostor

Exhibit 2 – The Cover

The cover address is the latter 1957 address, 47 West 63rd and not 767 Lexington Ave. It is the “wrong address” by at least a year for a Lexington, possibly two years.

Possibly a second print run of covers soon after the original stock ran out. Maybe it sold better than Lion expected, they still had stock of Lexington labels but needed more covers, which I would guess were a major expense compared with the cost of labels so low in inventory. Another theory.

Cover condition is better than the vinyl, another inconsistency. Somewhere in the past one or more owners who are a little careless in their handling of the black plastic – a few spindle-skates, paper and vinyl-on-vinyl scuffs, the odd light scratch. Why would they take such great care of a cover? It is a near mint cover. It doesn’t make sense, so I have another theory: the cover and record didn’t originally belong together.

Is there an answer? We consult jazz sage and mystic LondonJazzConfucious

Is there an answer? We consult jazz sage and mystic LondonJazzConfucious

LondonJazzConfucious says: When pieces of puzzle do not fit together, do not discount the possibility some pieces are from different puzzle.

Collector’s Corner

Source: Pre-owned record shop with a smart cosmopolitan West London address, occasional purveyor of odd Blue Notes of mysterious provenance.

This is a job for the vinyl squad. “Back in the good old days before Miranda, you could probably get the vinyl to talk: the old good collector / bad collector routine” Tell us about the Master and we’ll go easy on you. Then Hey Lexington, nice cover. Shame if anything were to happen to it. “Nowadays vinyls got all these rights”

This is a job for the vinyl squad. “Back in the good old days before Miranda, you could probably get the vinyl to talk: the old good collector / bad collector routine” Tell us about the Master and we’ll go easy on you. Then Hey Lexington, nice cover. Shame if anything were to happen to it. “Nowadays vinyls got all these rights”

So the vinyl remains an enema. No, thats thats something else, it remains an enigma. We may never get to the bottom of it.

Fortunately, Lexington or not, the record sounds amazing. Mobley swaggering with confidence of youth, everyone gels, and the bebop thing is still fresh and powerful. It wasn’t to stay like this forever, but it’s yours to enjoy, here and now.

UPDATE: BLUE NOTE SECRETS FROM BEYOND THE GRAVE

Thanks to Matty for sharing pictures of his 47 West 63rd St copy, which brings into sharp relief the similarities and differences between two pressings of the same recording. To make comparison easy I have mounted the pictures in forensic comparison mode (best viewed at full screen)

UPDATE 2. Matty’s copy close up ‘n’ personal

Side A

Side B

The position of the ear is a variable whilst the RVG and catalogue number are fixed, and the clock position of the whole lot varies. It confirms the ear is a Plastylite controlled input added to the mother or final stamper metalwork (as it stands proud), and varies from one stamper to another, as our posting detectives deduce below.

It feels like the call heard on the boating lake: “Time’s up, come in number six – err… number nine, are you in trouble?

Fascinating. Good work, chaps

Just for the record: Louis Hayes was 18 at the time of the session. The album got a four-and-a-half star rating in Down Beat Feb. 20, 1957. What a feat!

LikeLike

More than 10 years after the last post, I recently have acquired a copy of Six Pieces (in Fred Cohen’s Jazz Record Center in NYC), and I can confirm that the position of the ear varies: On my copy (63rd St labels without INC or R on both sides, DG, 177gm, but with 61st St address on the cover), the ear on both sides has a different position from your copy as well as from Matty’s. On Side 1 it’s left from the RVG etching, on Side 2 it’s between RVG and BNLP. So, I guess Plastylite must have used at least three different stampers in the second half of the fifties alone. Go figure!

LikeLike

I figure it is not stamper-related. I think the ear is on a different position on each copy, otherwise there would be same-position ear clusters. The ear is unique to Plastylite pressing, which is why it does not appear on Liberty pressings using original metal. My estimate of the number of copies pressed of each title suggests that on most titles, only one stamper pair was ever used. That’s my opinion, happy to hear others.

LikeLike

So you say that Plastylite applied the „ear“ stamp to every single copy manually, after the actual pressing took place (can“t think of any other way of getting individual positions of the „ear“ on every copy)? I wonder how (and why) would they do that on both sides of the record?

LikeLike

I may be wrong about the stamper business, I need to do more evidence-gathering on this, where I have multiple copies of Plastylite pressings of the same title, repressed over a number of years. I agree it seems logical for the ear to be “embossed” on a stamper, in which case it should appear in the same position relative to other etchings originating on the Van Gelder metal master, on each pressing with that stamper.

What is missing is any evidence of multiple stampers in use – no marking that identifies different stamper copies of the same title, like the 5 bar gate counter used by some other labels/plants. Sidewinder would be an ideal case study, as it sold tens of thousands of copies, which required probably at least five copy stampers for manufacture of that quantity. I don’t have multiple copies, and internet pictures rarely include etchings.

We know the ear is present somewhere in the runout on all Plastylite pressings. We also know it disappeared completely on pressing moved to other plants. We also know Liberty and UA took possession of some stage of metal formation (metal master, mothers, and or copy stampers) which have all the same Van Gelder etchings but no ear. Did Liberty/UA generate all new stampers from inherited original metal masters? If they used “old” Plastylite stampers, the ear would be there, and it is not. How the heck was the ear applied?

More homework.

LikeLike

What makes sense to me is that after a stamper was pulled from the mother, it would have the Plastylite “P” stamped into it, explaining why the “P” is actually embossed above the surface, not debossed into the vinyl. Every 500-1000 copies pressed from that stamper would have the “P” in the same place. Additional stampers would be pulled to press another 500-1000 copies and then would have the “P” stamped, apparently arbitrarily, in a different place. I once had two copies of a Blue Note with the “P” in the exact same place while the few other duplicate Plastylite copies I’ve had had the “P” in different places.

LikeLike

I agree Aaron, the evidence points to “batch production”. A comprehensive examination of ear-position permutations for each title (if that was possible) should reveal a count of how many batches were manufactured for each title, and by inference how many copies of each title were sold. That would be interesting! I reckon the number pressed per stamper is a bit higher than a thousand, but that is a different subject, for another time. What we need is a “classification of ear positions“, that doesn’t sound too much like the Karma Sutra.

LikeLike

There is a heavy vinyl collector on Instagram who alleges that the earliest Liberty pressings are Plastylite pressings without the ear. This would explain the heavier vinyl of the early NY Liberties.

Perhaps Larry the Plastylite Guy can provide some insight on when and how the “P” was put on the vinyl?

LikeLike

Larry has commented as a press operator, he knew little about metal formation at Plastylite. If you are out there, Larry, chip in.

Were early Liberty pressings by Plastylite but without ear? Liberty took over operations from Blue Note in early Summer 1966. They continued to use Keystone to print centre labels for several years, so that shows willingness to take advantage of continuity. It’s possible, but it’s a stretch.

Liberty bought All Disc and Research Craft pressing plants specifically to control their own pressing capacity, costs and quality. Even if Plastylite served as a brief interim pressing service in late1966, why would Plastylite drop the ear? It didn’t matter to anyone really, what is the motive to change the metal formation process to exclude it?

The weight of vinyl at around 160gm was common for pressing at that time, I think All Disc operated on equivalent quality industry standards. It’s a pity All Disc did not use any kind of stamp or etching to identify their own output. Liberty/Plastylite? I don’t have evidence one way or the other, it may be true, or it may not, that’s where we are without more evidence. A chronology of vinyl weight by release month of new titles may tell us something, but with reissues, its not possible

LikeLike

Sounds like a long overdue research project! As regards Horace Silver, I guess he sold quite well even in the fifties, so it wouldn‘t surprise me if Plastylite did several pressing runs over the time, maybe each with a new stamper (thus changing the ear‘s position). That would explain the numerous different label versions (including mixed pairs) one can find of this title on discogs.

LikeLike

Pingback: Horace Silver – 6 Pieces of Silver | RVJ [radio.video.jazz]

Pingback: Six Pieces of Silver: Horace Silver | DownWithIt!

I think we will be hard-pressed (no pun intended) to find variations in the matrix numbers of Plastylite era Blue Note runout grooves. I have hypothesized that the “-1” at the end of the matrix numbers for release 1539 is on every single Plastylite pressing of this record (I have two W63 copies, one with no R and the other with the R and both have the “-1”). The only variation seems to be the location of the “P”, which probably indicates a particular stamper, but IMO that doesn’t tell me anything about the potential fidelity of the pressing (long and incomplete story).

The only steadfast constant of this era is the “P” in the dead wax. If it has a P and it’s a 12″, it was pressed between ’55 and ’66.

The variations between pressings can get extremely confusing (I have been trying to make sense of this extracurricularly for a few months now), especially when you consider things like jackets getting swapped and labels getting pressed years before they were used.

LJC’s coverage on the case of the late, late Lexington (https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/2011/09/30/1520-a-lino-lexington-in-name-only/) was a revelation for me, that everything about this record except the flat rim, the weight, and the frame jacket was identical to an original. I came away from reading this feeling like you just have to accept the fact that trying to determine the age of a pressing has to be done on a case-by-case basis.

LikeLike

Not sure if anyone is still looking at this post, but I happen to have “Lexington on both sides” copy of 1539. My wife is a gifted photographer, so I’ll have her take some pics of the deadwax and I’ll send to LJC. Hopefully sometime in the next week.

LikeLike

Excellent – it is not often we get the chance to compare the runout detail of multiple copies of the same record, so there are a number of lessons which can be learned. This post has had more views than many, suggesting high interest. I will add the educational findings to the permanent pages of LJC, under Guide to Record Labels/Blue Note.That section has over 200 page views a day, worldwide.

LikeLike

Aha, the new close ups are up. Fantastic 🙂 I’m curious to know if there are other visitors here who have a copy of 1539 whose “ears” do not correspond with the “ears” on our copies.

LikeLike

Matty, my copy of 1539 has deep groove 47 West 63rd side 1/New York USA side 2 labels. The side 2 matrix etchings and “ear” placement are identical to your copy (not closer like LJC’s) but the “ear” on my side 1 is more centered between the RVG and BNLP.

LikeLike

Well, Aaron, pull out your camera and share your trail off close ups here on LJC with all of us! It shouldn’t be too difficult, if I can do it with my tourist cam, then you should be able to do it, too 😉

And hey, isn’t it weird that the differences in trail off ecthings of the “ear” only seem to apply to Side 1 of 1539…?

LikeLike

Will do when I have some time between work and holiday tasks. If you look at the spacing between the “B” and the “ear” on side two you will see that there is less space on LJC’s copy vs. yours.

LikeLike

You’re absolutely right, Aaron, it wasn’t until you mentioned it that I noticed it. So we now have confirmed that the position of the “ear” on side 1 and side 2 of both LJC’s and my copy differs. No let’s wait and see what we’re looking at when HD shares the close ups of his copy with LJC. It’s almost like watching an episode of Columbo 😛

LikeLike

I like the music on this piece of plastic.

LikeLike

Lander, you are not getting into the spirit of things! It is no longer about whether the music is any good. Meh. It is about whether it is on the “right” piece of plastic. 😉

Only kiddin’.

LikeLike

Although I find the conversation about matrix numbers, masters and production strategies interesting and entertaining, I thought I’d better put things in perspective :).

LikeLike

Absolutely right

LikeLike

By the way, LJC, and off topic: what’s wrong with the comment fields? Everyone’s writing seems to break off in the weirdest places, making reading a tad bit difficult…

LikeLike

My blog host WordPress have been making “improvements” behind the scenes again. Seems to have messed up text-wrapping. I have no idea why. I have just been on to them as their latest “improvements” to uploading process messed up the selection of images. The featured image wasn’t the main one, but one chosen at random. Crazy, but they fixed it this morning. I will get onto them. I think it is affected by which browser is being used. WordPress doesnt seem to like Explorer 9, because iE9 doesn’t support HTML 5, unlike Chrome and Firefox. If you view with Chrome as browser all seems OK. It is outwith my control. It is in the hands of WordPress. Technology! Can’t live with it, can’t live without it. If you switch explorer to compatibility view – basically iE8 – all seems OK, (though other things get a bit flaky)

LikeLike

I spoke to my local vinyl Confucius (an elderly guy from Chinatown I play mahjong with) and he patiently explained the following:

– If the recording label (in this case, Blue Note) packaged first pressings with second matrices and with third labels into fourth covers and used fifth inner sleeves, second address and third variant of Van Gelder’s imprimatur, we, the collectors, should add up the numerical value for each component (1+2+3+4+5+2+3), and divide the total by the number of pressing’s components (in this case, 20 : 7 = 2.857…) in order to calculate the generation of the pressing in question. So, what we have here would be a two-point-eight-five-seventh pressing of the Six Pieces of Silver (or, roughly, two silver shekels (plus change) for each generation of the pressing).

– Ah, but wait!. After I spoke to Confu, his nephew dropped by. He told me that the old man was in advanced stages of Alzheimer’s and often talking in a rather confusing manner. In fact, he said, there are two much more plausible explanations for the Great Mystery of The Six Pieces of Silver. We both agreed that the explanation # 1 (that Andrew had had one Agatha Christie and/or Sherlock Holmes novel too many) did not hold water and focused on alternative explanation: that Blue Note, while practicing economy of scale con giusto , used to order and stockpile individual components of the pressing (vinyl, labels, covers, inner sleeves, etc) ahead of actual distribution at different points in space and time by using different vendors, different stampers, different printing and pressing facilities, and quite possibly even different source tapes). These components would subsequently be packaged, combined and permutated ad nauseam randomly, at will and whim of the distributing agent’s (in this case: Blue Note’s) staff, and released to the hungry market as the market need arose, in time increments and intervals that could be measured in days, weeks, months, years and sometimes even decades. .

If the pieces of the vinyl puzzle do not match, it is typically because (to use modern-day analogy) a distributor was using Made-in-China pieces “X” of the puzzle and combined them with Made-in-Vietnam pieces “Y” before packaging them all into Made-in-Bangladesh cardboard box with Made-in-Mongolia labels affixed to it. The exact same thing happened to Blue Note, minus the overseas outsourcing: they used multitude of components, produced by multitude of local vendors, stockpiled in a multitude of locations, combined and packaged by multiple staffers (with, of course, zero thought given to internal consistency) and then, finally, brought to the market at different times, geographical points and under different circumstances.

In short, we are dealing with a complete production chaos.

Sure, We can do the historical and documentary research until we are chartreuse in the face (even where the bare-bones production didn’t care to leave much in the way of documentary evidence for posterity) , and we will probably be able to document that on such-and-such day, person so-and-so, operating from Blue Note’s distributing hub this’ n’ that packaged components of Coltrane’s Blue Trane by using this label, this slab of vinyl (remember, sometimes the labels would be glued, not impressed!), that inner sleeve and whachamacallit cover.

Ah, my dear Watsons, but THEN the real joy and excitement of vinyl deduction begins. After we have brilliantly laid out our theory, all of a sudden, out of nowhere pops out a copy of Blue Train (in all its Plystilited, deep-groove Glory), assembled at the said location at the same time, that somehow (gasp!) painfully refuses to conform to our hypothesis and sticks out like a sore thumb.

What now?

Should the hair-pulling and bellyaching begin, or should we count to ten and breathe into a plastic bag?

I know this will sound heretical and utterly disingenuous but I have to repeat:

– There is no such thing as the first pressinG (or, if there is, and none of us have ever seen one, because, by definition, only one copy exists). . There are only first pressingS (pluralia tantum),

– There are only earlier and later pressingS, and EVEN THIS is a very highly general and theoretical statement, without much connection to the physical reality or the realities of record collecting.

– In view of the fact that the vinyl LP record consists of multiple components (as little as four, and as many as twenty), we cannot truly talk of first, second and third pressings, UNLESS we have decided BEFOREHAND which of the components we have in mind to assess the “firstness” of the pressing. I, as a seller, talk about the label as a defining moment. Andrew talks about matrix. Joe Smith talks about Plastylite stamp. Hiroshi Takada speaks of the deep groove. Carlos Gomez talks of the missing trademark symbol. Valery Ivanov talks about the flat-edge. Kim Kwan-Jin talks about zip code on the label. None of these components were ever necessarily arranged in any kind of consistent, logical one-on-one causal/consequential relation to each other, for the same reasons I attempted to explain above. If you take my standard (label) as the quintessence of the first pressing, you will inevitably contradict someone who feels very strongly that, no, the deep groove (or the ‘ear’ stamp, or the RVG stamp, or….or….) is the dominant factor of the vaunted Blue Note’s FIRSTNESS. And yet, if you attempt to accommodate all parties and come up with some sort of Solomonic solution, you end up in major categorical and logical confusion and in massive self-contradiction.

And then, there is a matter of interpretation. We all assume that matrix A1 (or 1A) stands for the first (or earlier, or mother) stamper. But is it necessarily so? And where is the evidence? Says who? What if one record label’s 1A stands for chronological order and seniority of the stampers, but for another it stands for regional location of the pressing facility (for example, I was told that, on Columbia/EPIC/Harmony pressings 1A actually denotes their Santa Rosa pressing plant, not any generation of the pressing, per se — a claim too metaphysical, undocumented and speculative for me to even attempt to refute)

How do we know for sure that certain claims, statements, and general myths and legends or the collecting lore are, in fact, truthful and trustworthy?

Can we know it? Or are we simply forced to trust the “experts” and everything they say?

There can be a number of solutions to this infinite recursive equation and endless comedy of errors of the first pressings

(1) In a perfect world, each one of us would be allowed to determine his own first pressing by using a standard of his choice and liking, and nobody would have any problem with this.

(2) In a somewhat slightly less perfect world, the collecting body would reach a consensus that some elements of the pressing (say, stamper matrices) merit more attention and carry more oomph in determining the generation of the pressings than others. Who would call to order one such body and how would voting rights be distributed, I don’t have a slightest clue.

(3) In a totally messy and effed up world , such as the one we live in, there will always be a shouting match between those who feel that they hold the Noah’s Ark and the Holy Grail of vinyl firstness, and those who beg to differ. This is the situation we have now. One group accuses the other of indecency and untruthfulness, while the other scratches head and wonders if Franz Kafka is alive and well and chairs the Wold Association of Blue Note collectors.

To make things worse, there is not only no consensus on what precisely constitutes first pressingS, there is not EVEN A HINT of consensus on WHY it is important to collect first pressings. There are numerous schools of thought in this regard; that the first pressings are the best investment value; that the first pressings are, by definition, the best source of recorded sound there is (a statement I would categorize as grotesquely misguided and ill-informed); that the first pressings embody the original artistic and creative intent of the artist himself (an argument also highly problematic); that the first pressings represent best “mirror image” of the original master tape; or, simply, that my first pressing is bigger than yours 🙂 .

Ah, wait, That’s not all. A typical collector does not collect first pressings based on one merit alone. I confidently state that I speak for many other collectors when I say that I started collecting (and still do) based on any combination of these factors. I can collect first pressing, for example, because artist “A” and his title “X” sound way better on the first pressing than on any other sound medium (case in point: Ike Quebec on original Blue Note monos).

BUT !!!

I can ALSO collect original Ike Quebec Blue Note monos because they hold investment value; because the laminated covers look gorgeous and much better than the lowly CDs and because they are a joy to behold, and , yes, because this is how Ike Quebec originally must have heard them as he was authorizing his mono test pressings for production (I sold one of those a few years back). .

But that’s not all.

I can vary my arguments and my personal inner reasons from artist to artist and from title to title and sometimes from one artist’s title to another of his titles.. My collector reasoning does not have to be bound by some dogmatic, rigid dictum of the higher authority.

I can collect original James Carr albums because the sound embedded in those grooves blasts lousy compact disc versions to smithereens and because the late Soul crooner comes alive in my living room every time I play one of his LPs; I can collect Beastie Boys (whom I do not necessarily like) because they are fast appreciating in value; I can collect original American Beatles albums because the original American mixes were (until recently) unavailable in any other format. I can collect Arthur Lee’s Love’s albums or Velvet Underground albums because they possess a certain elusive and indescribable trippy ambience of the 1960s that no compact disc or 180-gram reissue ever will. I can collect Billie Holiday originals for sheer irrational sentimental value of for wanting to hold a physical object she herself might have held while she was alive. Or I can mix-and-match my motivations any which way I like and toss them around like dices and dreidels on a totally random basis, switching from one to another on a daily basis, or from one hour to another, or keeping them permanent and cast in stone in perpetuity..

Which then brings me to a conclusion of this tiresome and tiring tirade,

As absurdly as this may sound to a casual collector, in order to determine the first pressing of any particular title, we first must determine WHY we want to collect, and what material, artistic or spiritual value collecting records (or anything else, for that matter) holds for us (sadly, 99% of the collectors never openly ask themselves such question). It is not the absolute “firstness” of a particular piece of vinyl that drives our desire to collect it; it is exactly our inner motivation and volition that projects onto a vinyl disc and impels us to perceive a piece of plastic as “the first” of many. . We see in first pressing what we want to see in first pressing and WE determine what and why is the first pressing. Nothing more, nothing less. The object of our desire does not hold any absolute and superhuman capacity to impose its opinion, values or merits on us. It is we, the collectors, who ultimately decide what constitutes the first pressing, and why we want to own it.

And this, I think, is how its should remain forever.

Thank you for your kind attention and patience, y’all.

.

LikeLike

Lots of points here to ruminate on Bob, thank you. “Why we collect?” is indeed the mother of all questions. If you don’t know where you want to go, you will never get there, but then you won’t know you haven’t, if you know what I mean.

LikeLike

Thanks Andy!. The length of my submission is regrettable; here’s hoping some good will come out of it.

My point – despite the rambling and annoying length – is surprisingly simple. One has to DECIDE which element of the pressing (s)he will judge the pressing by, being that, obviously, diverse components of the LP pressings can be – and almost always are – of different age, vintage and origin and different collectors can LEGITIMATELY (!) judge the same pressing differently by using different sets of eyes, ears and brains. In order to do so, one has to determine what element of the pressing takes precedent over the others and why. And in order to accomplish this, one has to know why he is collecting vinyl. There simply is no point in arguing with a fellow collector unless we are using the same language, and unless we know why we are quarreling.

Alas, this may be too much to ask for 🙂

My comment is expected to become a first draft of my “Misconceptions of Collecting” article , which I will hopefully finish at some point in the next six months.

LikeLike

“To make things worse, there is not only no consensus on what precisely constitutes first pressingS, there is not EVEN A HINT of consensus on WHY it is important to collect first pressings.”

YES.

LikeLike

Yesterday I was cleaning up a recently purchased early Liberty/serrated edge pressing of “The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 2” which I had bought on the basis of an advertised “etched RVG” indicated in the listening.

Unfortunately, upon flipping the LP over to clean the B side, I saw something I shouldn’t: “VAN GELDER”. A remaster, and a late one at that. After drying away my tears, however, I noticed that the matrix ended in “A-1”. This, for me, is finally proof enough that this was RVG’s system for noting new masters (for Blue Note, at least).

Of course this does nothing to answer the question you raise: Why did Van Gelder cut a new master? Certainly the simplest answer is that the original was unusable due to loss or poor condition. This is quite plausible and perhaps no further explanation is needed.

However, during the trials and tribulations of trying to hunt down Prestige LPs that don’t sound like they are coming out of a tiny guitar amplifier upon playback, I have became aware that RVG was seemingly constantly cutting new masters for Mr. Weinstock. Sometimes only one side has been remastered and other times he seems to have cut new masters for both sides at once.

It seems to me that there were four potential reasons for doing this:

1. The original master was lost or in poor condition

2. The title was being reissued, which presented a good occasion for new mastering

3. RVG had new and better equipment and cut masters for improved sound quality

4. There were pressing issues caused by the way the original master was cut

It seems to me that at some point, either at the behest of Bob Weinstock or of his own volition began recutting all the ‘etched RVG’ era Prestige masters. A quick glance at popsike will reveal that many of the 7000 series LPs exist in both “etched RVG” and “stamped RVG” flavors. The more Prestige LPs I run across, the more it seems to me that this was a systemic effort.

As all too many of us know, Prestige pressings seem particularly prone to the telltale nasty hiss of groove wear. In my quest to find decent copies of some titles, I’ve gone through two or three (and in a few cases even more) before I found a copy with minimal groove wear. For many Prestige earlier titles, it seems far more will have groove wear than not, even copies with no other condition issues.

After a while, I began to notice that certain LPs always seem to exhibit groove wear in the same spots. A good example is the lethal one-two punch on many Miles Davis LPs of sforzando Harmon mute coupled with inner grooves. The last few bars of “All of You” on “Round About Midnight” is a case in point. I’ve seen at least two near mint condition copies of this title, one still in the original plastic liner and NM sleeve, that were flawless except for groove damage in this trouble spot. After seeing this again and again, my conclusion is that the mastering is the ultimate cause.

I’ve also seen this problem with the Atlantic LP “What’d I Say” by Ray Charles. There is serious sibilance on the vocals on the eponymous opening track, and again every copy seems to have corresponding groove wear at these points. Subsequent masters have the treble rolled off in attempt to address this, and do not have the same problem although the EQ’ing has a negative impact on the overall impact of the track (the recent HDtracks release of this title seems to be made from the EQ’d tape).

It’s also well documented that early LP cutting engineers would often roll off the treble as they reached they approached the center of the disc in order to address this problem. All this has leads me to suspect that at least one of the reasons for RVG’s remastering was to address similar issues with the original masters.

At some point in the 50’s (I can’t seem to pinpoint exactly when) Rein Narma developed the Fairchild 660 limiter which was explicitly developed to address problems such as sudden bursts of high frequency noise. Narma was the legendary engineer who modified Van Gelder’s Telefunken U47s microphones (he purchased some of the first units imported from Germany) so that they could handle the extremely loud volumes of closely mic’d horns which allowed Van Gelder to be one of the first engineers to employ these state of the art microphones for recording jazz.

Narma has stated that one of the first, if not the first, of his new Fairchild limiters went straight into RVGs studio:

http://bit.ly/SDUL4N (Interview with Rein Narma – see page 2)

My current working theory is that this prompted Rudy Van Gelder to revisit his pre-Fairchild masters when new pressings of these title were ordered by Prestige, Blue Note, etc. By cutting new masters using the Fairchild, he could address the problems with high frequency noise. It’s also worth noting than RVG’s earliest masters are often his loudest and that later masters show reduced signal level, presumably also to address problems with groove wear.

Of course, this theory doesn’t explain all of the remastering by a long shot. I have a blue trident copy of “Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet”, for example ,which has a VAN GELDER remaster on side A and the original 1959 RVG master on side B. Also, there are certainly still seem to problems with loud high frequency noise on titles issued after the “etched RVG” era such as “Steamin’”.

Apologies for yet another protracted post. If brevity is the soul of wit…

Anyway, I hope there is some interesting/helpful info in there somewhere. I don’t set out to write such encyclopedic posts, honestly! 🙂

LikeLike

sforzando

Brilliant word, completely unknown to me, betraying my lack of schooling in the finer arts. I shall seek to add this to my repertoire of French and Latin.

LikeLike

Those of us in the music profession often casually refer to this as “blastissimo.”

LikeLike

Thanks Matty, fascinating. The A-1 stamper caught in the cross-hairs? This one could expose a lot of the workings of Blue Note production. I need to spend more time lining up your photos with my own. Great stuff.

LikeLike

It’s my guess that the Plastylite “ear” was etched in the wax of the negative of the eventual stamper, ’cause to me it always looks as if the “ear” seems to ‘come out’ of the vinyl, where everything else, i.e., the groove and Rudy’s etchings are actually in the vinyl.

Still it is clear that the “ear” on the A-side of my copy is positioned in a different spot than it is in your copy, but the RVG etchings are identical. Maybe I should re-shoot the close ups of my trail off etchings in order to create better matches with your close ups.

Oh, and before I forget: my copy weighs 198 grams on our kitchen scales. Not the most accurate scales on the market, so maybe the real weight of my copy is 200 grams.

LikeLike

Interesting! The weight is close!! These could be from the same batch.

If its any help with deadwax, I use head-on in black and white mode, and overexpose by three stops to capture the runout engravings.

LikeLike

Hmmm… Let’s see what I can manage with my tourist cam. To be continued; once my renewed snapshots are finished, I’ll pass them on through email. Who knows it may be the first time that this has been done in word an image online 😉

LikeLike

For what it’s worth, LJC: I would love to see an article on the Right Way to Photograph Your Blue Note Records®. Your images are really of extraordinary quality and I would love to see a glimpse into how you achieve it.

LikeLike

Just updated for the latest all-in-one label and runout technique, the secrets of shooting records for LJC

https://londonjazzcollector.wordpress.com/about/ljc-shoots-records/

Warning. requires use of entirely manual settings in an SLR camera, and a working knowledge of image editing in Photoshop. Not for the faint-hearted!

LikeLike

AHA!!

We now have the opportunity to do a direct one-on-one comparison of trail off etchings of two different pressings of the same record, in which Rudy van Gelder’s etchings (the RVG and the catalogue numbers) match each other exactly but with clear evidence that the position of the “ear” differs on the A-side of my copy.

I have a copy of 1539 with 47 West 63rd – NYC and the deep groove on both sides, plus no “inc” and no trademark “R”. The address on the back of my copy is also the same as on LJC’s copy.

But as as said: the position of the Plastylite “ear” on my A-side differs. Please feel free to unleash some fresh detective work on these two copies by comparing LJC’s photos above with the photos of my copy, available HERE.

Maybe A-side stampers wore out faster than B-side ones? 😉

LikeLike

Oh, and one piece of advice to view my photos: watch them in “slide show”!!

LikeLike

My post updated with your photos, in Forensic mode

LikeLike

Fascinating stuff!

According to my copious speculation, this proves that the Plastylite ‘P’ was not etched in the master. The question then is was the ‘P’ etched in the mother or the stamper.

I had never noticed it before, but after pulling out a few pressings and running my pinky across the ‘P’ mark, I think Mattyman is onto something. The ‘P’ does seem to protrude from the LP rather than being recessed, meaning it was introduced during a ‘positive’ phase of the replication process.

Since we have excluded the master, it seems to me this proves to me that the Plastylite “P” mark was added to each stamper. Therefore, the position of the “P” mark can be used to differentiate (but not establish the order of) stampers.

LikeLike

Glad to know I’m not alone in this assumption, Felix! It must be in the stamper

I guess, ’cause the stamper is the ‘negative’ that presses the grooves in

the vinyl, including the etchings of Van Gelder. If then the “ear” seems to come ‘out of’ the vinyl (or protrude), this must mean that the “ear” was etched

in the stamper. After all, on a negative, the groove is a ‘dyke’ and Rudy’s

etchings are ‘feelable’ like Braille. Catch my drift? 😉

LikeLike