Every record tells a story, this one is no exception. It just needs someone to find it, and tell it, the record is merely the jumping off point. So set your time-transporters for the Summer of 1955, you may need to bone up on your beat slang to fit in. If you dig it, man, it’s crazy! You’ll be making the scene! On second thoughts, zip-it, keep a low profile, and pull your hat down.You do have a hat, don’t you? No, not a woolly one.

Every record tells a story, this one is no exception. It just needs someone to find it, and tell it, the record is merely the jumping off point. So set your time-transporters for the Summer of 1955, you may need to bone up on your beat slang to fit in. If you dig it, man, it’s crazy! You’ll be making the scene! On second thoughts, zip-it, keep a low profile, and pull your hat down.You do have a hat, don’t you? No, not a woolly one.

Selection: Bohemia After Dark (Oscar Pettiford) self titled.

. . .

Artists

Read the line up carefully, it’s an important part of the story.

Nat Adderley, cornet; Donald Byrd, trumpet; Cannonball Adderley, alto sax; Jerome Richardson, tenor sax, flute; Horace Silver, piano; Paul Chambers, bass; Kenny Clarke, drums. Recorded NYC, June 28, 1955

How the line-up of this 1955 Savoy recording date came about is a story in its own right, for which I will borrow some excerpts from Cary Ginnel’s excellent biography of Cannonball, Walk Tall – The Music and Life of Julian Cannonball Adderley. Rather than retype the story, or indeed plagiarise Ginnel’s work and take credit, I will experiment with using a few caps from the book, undertaking the continuity links myself. Fair Use disclaimer.

One evening, in June 1955, bassist Oscar Pettiford’s band was due to play at the Café Bohemia, but his regular (alto) player Jerome Richardson went missing, supposedly as a result of another engagement. (He is also missing from the group photo above) Missed dates were not unusual among musicians, given the widespread use of narcotic and the chaotic lifestyle of some musicians, so it was common event to need to seek stand-ins.

News of Adderley’s performances spread like wildfire, and impressed Miles Davis so much that he determined Cannonball would subsequently join his 1st great Quintet. Kenny Clarke was soon scheduling a recording session for Savoy producer Ozzie Cadena, to be recorded at Hackensack, by Rudy Van Gelder. However the final line up saw some unexpected last minute changes:

So we hear the recording debut of Paul Chambers, age just 20, in place of Oscar Pettiford, basically with Pettiford’s band, recording Pettiford’s composition, “Bohemia After Dark”. To signpost the absence of Pettiford himself from the session, adding insult to injury, the band dedicated one track composed by the two Adderley’s and played over the changes of Sweet Georgia Brown, which they appropriately, or ironically, titled “With Apologies To Oscar”.

Apologies to Oscar, indeed!

Pettiford left the stage for the last time in 1960, at the age of only 38.

It was Kenny Clarke’s recording as actual leader, but Adderley’s rise to fame edged him off the credit list, perhaps the final push that set in motion his move to Europe in the following year, 1956, where he settled in Paris, took up playing with Bud Powell, before becoming a permanent fixture in the Francy Boland Octet and Big Band (much to our enjoyment)

Music

Bohemia After Dark is a jazz standard, recorded by many artists as well as being part of Cannonball’s long time repertoire. Stylistically pacy Hard Bop with a fine Pettiford tune (joining his great tunes like Oscalypso) that captures the lively, briskly-moving urban night-scape of 50’s New York. People out on the town enjoying themselves, bright lights, car horns, the sound of live jazz pouring out of clubs onto the street, lively music for lively people, not yet the next stay-home generation slumped on sofas in front of TV sets.

My favourite Bohemia is Sahib Shihab’s baritone-driven version, which captures the spirit of Pettiford’s tune. Some versions, like Adderley’s Quintet in San Francisco, are taken at too fast pace for a tune with already plenty of rhythmic drive. What is particularly impressive for 1955 is the quality of Van Gelder’s Hackensack recording. More on this in Collector’s Corner, see below.

Vinyl: London (UK Decca) LTZ-C.15047 UK issue of Savoy MG 12017

Original release December 1955, 1st cover, Savoy blood red label, deep groove, RVG hand-etched, Kenny Clarke nominally leader gets top billing.

Someone famously can’t spell RESTRAURNT, or maybe that’s just how they spell it downtown NooYoik.’ Kenny Clarke in largest capitals, but before long, alternative covers begin to note “featuring Cannonball”.

Someone famously can’t spell RESTRAURNT, or maybe that’s just how they spell it downtown NooYoik.’ Kenny Clarke in largest capitals, but before long, alternative covers begin to note “featuring Cannonball”.

Three alternative covers followed: The Boys In The Band (Hey, get the drinks in, Cannonball, mine’s a large whisky) ; “Model: Gosh, It’s Awful Hot In Here, mind if I slip into something more comfortable?” (note strategically placed letter B), and the New York Skyline (It’s after dark, it’s getting late… yawn…I think I’ll turn in). Bohemia was, of course, a region of the Czech Republic bordered by Germany, Poland, Moravia, and Austria. Material enough for European History Month, but not thought sexy enough to make it to the Savoy cover. Cary Ginnel picks up the cover story

Original Savoy mastered by Rudy Van Gelder, remastered by Decca and released in the UK in January 1957. Despite using the same photograph of the band as the second US Savoy cover, the British release, deliberately or mistakenly, omits the legend “featuring Cannonball”. Leaving British jazz fans collectively scratching their heads: whose album is this? Under whose name do I file it? I think under “Cannonball”, or more correctly, Julian “Cannonball” Adderley.

Collector’s Corner

A recent question from a reader about the “Blue Note sound” got me thinking about the contribution of the studio environment in which they were recorded. We have had a lot of excellent research by DGmono on Van Gelder’s transition from mono to stereo , so I don’t want to go there.

Van Gelder recordings can be separated into those at his parent’s house home studio at Prospect Drive Hackensack, starting around 1953, last recording July 1, 1959 and those following the move to custom-build Englewood Cliffs first recording July 20, 1959.

What intrigued me is how, in the mid ’50s, Rudy could produce such amazing quality recordings, in such an unpromising setting as a domestic living room. That points towards the question of room acoustics, microphones and most important, the type and number of microphones and their positioning. I was listening recently to the Cannonball Adderley Record Day title of previously unreleased Live in San Francisco, 1966. It sounded rubbish, and the penny dropped why it was mono at a time stereo was standard. It was mono because the radio DJ (not an engineer) who recorded it almost certainly had just one microphone, in front of the band. Moral, when a live recording after say 1965 is ONLY in “mono!” expect bootleg quality!

Whilst Englewood Cliffs, with its cathedral-like acoustic space, high ceiling, and EMT plate, produced a sense of “air” around the musicians, especially in stereo, Hackensack produced a sense of intimacy and cohesion, the musicians were virtually on top of each other, mostly in mono. Though Van Gelder kept his techniques hidden from public view, I figured some picture research might throw some light on What Rudy Did.

The revelation came not from anyone actually photographing the Hackensack studio, not found, but from pictures of artists recording there, where in the background unintended detail revealed what was going on at the engineering level. So here is Chapter One of my What Van Gelder Did story.

Van Gelder’s parent’s house 25 Prospect Ave, Hackensack, New Jersey

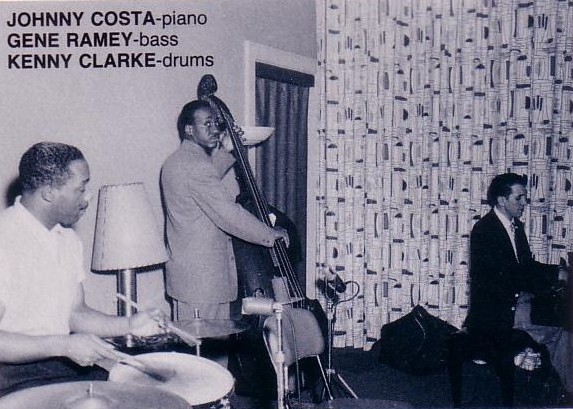

Interior décor, leaves something to be desired, retro table lamp luckily back in fashion, but the warmth and intimacy of sound captured by adapted German valve microphones, and close proximity of the musicians in a small space with a low ceiling, that’s Hackensack sound. By a strange coincidence Kenny Clarke is pictured below, recording at Hackensack

Close-miking: mike hovering over a cymbal, where the sibilance and high frequencies are captured; also just in front of the bottom end of the double bass body, capturing the bottom-end frequencies; and below, mikes over piano body. Neumann U-boat forty something valve microphones. Drapes across the windows, concealing wooden shutters, a little damping from them. I dare say, the instrument mikes are picking up a small amount of sound of the other instruments in close proximity, reflected off close room walls and low domestic ceiling. Intimacy, cohesiveness.

Herbie Nichols at the keyboard, two possibly three microphones posed, hungry for sound.

Most prominent among the microphones used by Van Gelder was the Neumann/Telefunken U-47, in manufacture between 1949 and 1958. This had an independent power supply (psu pictured below next to mike) and at its heart (inset right) the VF14 tube amplifier, a pentode tube in a steel housing. Only a third of VF-14 tubes manufactured passed the stringent tests for microphone application, which were then stamped “M” (“mikrofon”). The signal received by the VF-14 amplifier is instrument moving-air captured by the fluctuations of a dual diaphragm capsule, the famous M7. This capsule can be set for cardioid (directional) or omnidirectional mode. An engineer could explain the choices Van Gelder made as regards close-miking, and the omnidirectional mode, which captures more natural room ambience.

The other mike also hovering over the piano body is what looks like an RCA ribbon microphone, older generation technology before the arrival of condenser valve/tube mics.

Ribbon mics, which came of age in the 1930s, feature an extremely thin strip of metal (often aluminum) suspended in a strong magnetic field. The ribbon acts as both the diaphragm and the transducer element itself, providing the same kind of sensitivity and transient response you’d expect from a condenser, but with a wholly different character. It looks like Rudy is running a two-horse race, in which a bet on both ensures you have a winner.

But where does Englewood Cliffs air come from?

Englewood Cliffs

Photos borrowed from New Jersey.com

As internet links can often get broken I have uploaded a permanent set of these important photos inside Englewood Cliffs

Don and Maureen Sickler maintain the Englewood Cliffs studios for posterity.

Notice Englewood Cliffs large acoustic space and vaulted beam-and-purlin construction roof design, providing an acoustic chamber intended to add reflections to the sound. It was modelled on the Columbia 30th Street “Church” recording studio (pictured below) which offered over 5,500 square foot acoustic space with 60 foot high ceiling:

Columbia’s secret acoustic weapon was also a reverb chamber below. The hard-walled basement provided an auxiliary reverberation chamber, layering its ambience on top of the natural acoustics of large spaces. The signals from the left and right channel studio mikes were piped down into the chamber and back up into the mixing desk.

Englewood Cliffs acoustic space , pictured at the launch of the “lost” Coltrane title Both Directions at Once. The ceiling construction is made of cedar panels and Douglas fir arches

The more impressive change between Englewood Cliffs and Hackensack owes much to the larger acoustic space, the exclusive use of close condenser microphones, and the adddition of an EMT Plate Reverb, – “the use of reverb, whether natural room, chamber, or plate, practically defined the “hi-fi” era of music”

What is an EMT plate? German company EMT (Elektromesstecknik) made a huge breakthrough in 1957 with the release of the EMT 140 Reverberation Unit—the first plate reverb. EMT in its day was by far the most popular developer and manufacturer of artificial reverb solutions for the recording industry, forerunner of the field.

Englewood Cliffs it has been confirmed took delivery of an EMT plate. No photos found online show it, because no-one in their right minds would think it important to show.

The story pauses here. I am not an engineer, but I sense that the story is here: Van Gelder created the most beautiful sound experience, which I get it every time I mount a record on the turntable. The explanation how is elusive.

Hope you have enjoyed the ride so far. it is all about discovery and creating knowledge that is useful to people. If you can contribute anything, the floor is yours. If you have taken anything from it, that would be nice to know. If you want to know more, such as what?

I am all ears.

LJC

“Read the line up carefully…” we are instructed at the beginning of this episode. I was distracted, day dreaming, doodlin’ away or something and thought I saw – “Nat Adderley, COMET” Somehow that’s fitting, but of course it really reads CORNET, which I sometimes confuse with its cousin the trumpet. Truth be told I’ve been fretting all day about TRUMP, and that is distraction. America has lost a lot of Jazz and now we’re losing a lot more than that. No politics here? Tell that to to the Jazz revolutionaries who are still spirits where Bohemia was.

LikeLike

I think in the picture with the names and ages you have Ozzie Cadena, producer/A&R, labeled as “Jerome Richardson”. The man labeled “Horace Silver” looks more to me like what I imagine Jerome Richardson might have looked like in 1955 . Thanks for all your fantastic work on the blog.

LikeLike

Cary Ginnel, describing the group picture, refers to Horace wearing “a striped golf shirt”, so from this and other pictures I have seen, it’s definitely Silver.

However you may be right about “Jerome Richardson”. A little more homework suggests Jerome (of whom I know little) was Afro-American, so this more pale chap by deduction is Ozzie Cadena. Can’t find a young photo of him but I am sure you are right, thank you.. Question is, where the hell is Richardson?

LikeLike

Great post. Very thought provoking and informative. Thank you for the link to the Sickler movie and thanks to Shaft for the link to that wonderful article by Dan Skea. He makes the point that the “Blue Note Sound” should be called the “Van Gelder Sound” and gives three examples from BN, Prestige and Savoy, each recorded at the same time period in Hackensack. I don’t have the originals on two of the three so a direct comparison is impossible, but I never found the sound of Savoys, be they red or maroon labels, to be much good. They seem muddy and unappealing. I chalk it up to the cheap post production from that SOB Herman Lubinsky. I have a few Savoys from the UK on London and even though they don’t have RVG in the dead wax, they sound superior to any domestic issues. Quality vinyl and attention to detail help realize the superior sound captured in Hackensack so that the Van Gelder Sound can be properly heard.This was accomplished most often with Blue Note and almost not at all with Savoy.

LikeLike

all of my questions answered… with the exception of why pettiford wanted silver fired. i believe this was mentioned in silver’s autobiography, but alas i forget it. if i recall, it was a mere misunderstanding and pettiford decided he hated silver… they later reconciled. or is this monk that oscar hated? i have read too many bios.

LikeLike

the pianist shown after Johnny Costa looks to be Herbie Nichols.

Thank you LJC for this wonderful entry. Nice piece of jazz history, the Savoy label intertwined with RVG’s engineering.

LikeLike

What a great track. Reminds me a bit of Charles Mingus at his finest.

LikeLike

There is more to say about Hackensack. It did not have the dreaded plate EMT reverb but rather a natural acoustic. I remember reading somewhere about the possibility to open up the space to get some:

From a PDF: https://currentmusicology.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/13/2015/03/current.musicology.71-73.skea_.54-76.pdf

Author: DAN SKEY

When Van Gelder graduated from college in 1946, his parents had just

built a new home in Hackensack at 25 Prospect Avenue, on the corner of

Thompson Street. Among the unusual features of the house, a one-story

ranch style that would soon become fashionable throughout the country,

were its cinder block construction and central air conditioning. In planning their new home, Van Gelder’s parents were mindful of Rudy’s keen

interest in recording. In the space that might otherwise have been an additional bedroom or study, they had architect Sidney Schenker design a

control room instead. This room was separated from the living room by

a large glass window set into the concrete block wall. The window was

double-paned for greater sound insulation, with one pane angled slightly

off the vertical to eliminate reflective glare. Under this window, a hole

through the wall served as a conduit for microphone cables.

As it happened, this particular living room turned out to be an ideal

venue for recording small-group jazz. The ten-foot-high ceiling made the

room seem more spacious than it actually was, while the wide archway opening into the adjoining dining room, in which sound waves could reverberate, offered an added dimension. Corridors leading off toward the kitchen

and the bedrooms provided additional air columns of varying proportions.

“Acoustically it sounded nice,” said Rudy. The room “had little hallways and

little nooks and crannies going off. It was really nice. Nice place to record. I

made some good records there” (quoted in Sidran 1995:313). In the end,

due to a combination of factors that no one could have foreseen or predicted, the Hackensack living room’s uniquely favorable physical configuration and acoustical properties helped Van Gelder achieve a sound that

would eventually be heard, recognized, and widely emulated.

LikeLike

I have to add that RVG must have used some other reverb in Hackensack i.e. not an EMT reverb but some other device. Anyway it can quite easily be heard in early Blue Notes. Apparently Alfred Lion was not always so happy with the reverb…

LikeLike

I don’t have a dog in this fight.

DGmono has written Rudy had a reverb facility at Hackensack. Whilst the alcoves and fireplaces might have introduced “echo” during recording, I do recall reading Van Gelder could add reverb in post-production. I believe reverb, whether these plate things or chambers , was necessary for recordings to sound natural, moving air.

I also read Englewood Cliffs “took delivery of an EMT plate” (no date or model was mentioned, so who knows) . Again, I know nothing. I read Dan Skea’s Columbia project, but found nothing definitive about the use of a Plate.

Welcome any knowledge from anywhere.

LJC

LikeLike

Hi again,

Well I posted both as Shaft and erroneously as Anonymous. My guess is that in the second studio at Englewood Cliffs he got an EMT as stated and that is what we hear from the recordings there. It is probably of better quality that the on he used in Hackensack which could actually be a more primitive spring reverb and can be heard in RVG’s mid 50’s recordings. It’s not very good and quite annoying if you start listening for it ( – so please don’t) 😉 .

About the natural acoustics in Hackensack I think it was adding somewhat to the reverb but not enough. But better to have some natural acoustic reverb that none (and probably make the studio/living room less warm and “stuffed” also.

LikeLike

I have the Savoy (topless edition ) and just picked up a 1980 Japanese issue on Arista ( with the After Dark cover ). To my ears the sound quality is superior on the Arista , the treble has been advanced so you can clearly hear the Clarke symbols etc without taking away the from the rest of the sound spectrum . I agree it was a good session except I felt Donald Byrd had a bad day , his solo on “Apologies” needs an apology in my book

LikeLike

Thoughtful comment re Byrd. A lot of these guys were so young at the time, you sometimes hear solos going astray. Equally they take risks maybe they shouldn’t, which sometimes don’t work out, but are a joy when they do. Tina Brooks is my favourite example. He gets goes out on a limb but manages to grab a branch to stop his fall, and he’s off in another direction up the tree. Give them a year or two and its all beautiful.

LikeLike

My Savoy original (topless babe cover) has the noisy surfaces of a record well loved or pressed on old recycled raincoats, I am not sure which. A wood glue cleaning barely improved it. But I have played this record to death since I picked it up in an estate sale for a buck 5 years ago. One of my favorite jazz records on the planet, along with ‘Hampton Hawes Trio’, ‘Jazz At Massey Hall’, The ‘Swinging Mr. Rogers’, ‘James Dean Story’, ‘Sweet Smell Of Success’ OST, ‘Having A Ball’ (Cy Touff) and Lennie Tristano’s ‘Live at Confucius’

LikeLike

Hello LJC: Have you had the opportunity to compare a Savoy pressing with the London?

LikeLike

In a word, no. I do have just a few other original 50s Savoy titles, and they are a mixed bag, on the whole, somewhat unsatisfactory, lacking the presence I would expect. Savoy reissues from the ’70s and beyond are even worse.

LikeLike

I can vouch based on LJC’s dub of this track that the London is somewhat brighter above 3khz than the Savoy. The latter has a really wet midrange and I find I can hear the “room” better with that midrange-not-treble emphasis. But I could see why others would find the Savoy muddy. I’m the guy who loves Curtis Fuller records so my emotional response will depend on those mid-and-lower frequencies.

I have a U.K. (London) copy of ‘Swinging Mr Rogers’ and I keep it only for the novelty, I much prefer the comparatively midrangey Atlantic US press.

LikeLike